By Abigail Green-Dove

![]() Each piece in Yaron Dotan’s Sight Unseen is a challenge of perception. Combining ink with paint, optical drawing with figurative work, each piece poses the question, Am I seeing it all? A glance at his painting “Narcissus” will reveal the black and white ripples of a rock hitting water. Look for a while and a second image appears: the pink back of a woman, staring into a pool of undulating, blue water. Look longer, and eyes appear, in black and white and upside down, staring back at you. Blind in one eye, Dotan’s paintings are, in one way or another, the portraiture of a man struggling to see.

Each piece in Yaron Dotan’s Sight Unseen is a challenge of perception. Combining ink with paint, optical drawing with figurative work, each piece poses the question, Am I seeing it all? A glance at his painting “Narcissus” will reveal the black and white ripples of a rock hitting water. Look for a while and a second image appears: the pink back of a woman, staring into a pool of undulating, blue water. Look longer, and eyes appear, in black and white and upside down, staring back at you. Blind in one eye, Dotan’s paintings are, in one way or another, the portraiture of a man struggling to see.

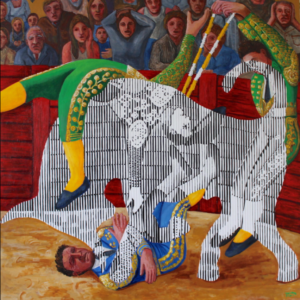

In our age of “alternative facts” and social media feeds that don’t show us what is real but what Facebook or Twitter have algorithmically pre-determined is the reality we want, each of Dotan’s paintings responds to questions of fact. At times it isn’t the struggle with facts that emerges, but the desperate desire for facts at all. In the perfectly named “They saw what they wanted to see,” we watch an audience respond to the carnage of a bullfight, except the bull’s existence itself is a question. The stunned faces in the crowd and the bright yellow and green embroidered pants of the bullfighter slung over the bull’s back tell us one story, but the bull—a black and white optical drawing through which you can half see the animal and half see the upper half of the bullfighter—tells us another.

Sight Unseen is timely and challenging. Each painting: a puzzle of vision; a puzzle of darkness or light. We the gallery goers are the modern, television-watching equivalent of the figures in the crowd of the bullfight, raptly watching questionable signals.